Compelling case studies doesn’t simply relate how a customer used and benefited from your service/solution/product. That’s a testimonial. There’s no “oomph” there, nothing to excite the reader, very little to make it memorable—and nothing that puts the reader (your prospect) into the featured customer’s shoes. If you can’t do that, what’s the point of investing in a case study?

Rather, compelling case studies revolve around the customer as a hero. They’re about someone (and you do want to focus on someone, even though most B2B case studies will be about a company) who overcame the forces of legacy processes, the strangulation of tight budgets, or the chaos of mismatched systems. That will highlight your customer’s plight and invite the reader to put themselves in the protagonist’s (your customer’s) shoes.

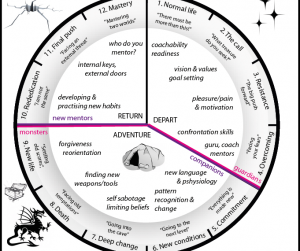

The best way to structure such a story is through the classic “hero’s journey,” or monomyth. Audiences are innately familiar with that structure. They see it all the time in movies, TV shows, and books; Star Wars is the most widely cited example, but most stories that feature a hero doing epic things follows the structure. Therefore, it’s a comfortable story structure that the reader can easily slide into. It allows them to envision themselves as the hero improving their situation.

A brief background

Joseph Campbell, an American mythologist, writer, and teacher created the 17-step “hero’s journey”—which he called the monomyth—and wrote about it in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Many years later, Christopher Vogler condensed those stages down to 12 to show Hollywood how every story ever written should—and almost universally does—follow Campbell’s pattern. We’re not going to go into all 12 of them, because most of them are irrelevant when you’re writing an 800- to 2,000-word customer success story instead of a forest-devouring trilogy of novels.

But there are some steps we can lift from his structure that fit perfectly with a case study. And those are the ones we’re going to look at.

The steps of the journey that we can incorporate into case studies

Every hero’s journey begins with the ordinary world and the call to adventure.

Luke gets a message from a beautiful, mysterious woman, an omen that the intergalactic war has found his peaceful (ordinary) planet. Soon, he’s sucked up into it. Daniel Russo moves to a new town and falls for a girl who has a jerky, overly protective boyfriend.

The sales team has been using the same CRM for years, but the system hasn’t aged well, and now it lags when users are entering data. The system has spawned multiple cumbersome processes (an inefficient setup). And today’s sales force needs a system with mobile capacity. So, the IT or CRM leader ventures forth to find a new and better solution.

By starting with the ordinary—in an office, for example—you paint a picture of normalcy that readers can relate to. Most professionals in your audience know exactly what it’s like to deal with outdated programs that eat up productivity and spit out frustrations. And we’ve all experienced the anxiety and uncertainty that comes with venturing into the unknown. We remember how nerve-wrecking that was, how we were beset with uncertainty at every step. So when we see someone else going down a similar path of uncertainty, we instinctively root for them.

You need to talk about the challenges plaguing your hero, some impetus that causes him/her to say, “Enough is enough. I must venture forth and solve this pain point!” (Although they don’t have to be so grandiose about it.)

Then the hero meets a mentor (Obi-wan Kenobi, Gandalf … but they don’t all have to be wizards) or an important tool.

This mentor provides them guidance in solving their problem/challenge. In case studies, the role of the mentor is played by your company, or its solution/product/service.

There’s the Road of Trials.

This will be unique by each case, although there some common categories: You can even talk about the initial missteps the hero took in selecting a tool—maybe they tried another solution and it didn’t meet their needs, or made things worse; maybe they had trouble deploying the solution and needed to use the premium support you offer; maybe some of the users were reluctant to try something new. This is a delicate balancing act, because you can’t make your customer look bad, but you certainly want to keep the story compelling by presenting obstacles they dealt with.

Notice that in the examples of trials I mentioned (all taken from real case studies I’ve written), the mentor (you as the vendor/consultant) offers the path around those obstacles. The solution that does work; the great premium customer service that makes implementation a breeze; a solution so easy, even users who are used to doing things the old way are happy to use this new tool. That makes a compelling case study and positions you even more as the must-have solution for the reader.

Then, there’s the Ultimate Boon and the Master of Two Worlds (from Campbell’s longer structure).

The ultimate boon is the achievement of the goal. It’s what the hero went on the journey to get. Having completed the journey and achieved his/her goal, the hero is now a master of both natural and supernatural world. He/she can pass over the threshold between the two without further trial. This cements the hero’s position as the ultimate power.

Or, in the case of B2B case studies, the hero gains the service/solution to overcome the pain points and achieve the benefits he or she desired—and, hopefully, some unexpected benefits, as well. That makes them the master of the CRM game, for example, and gives them the ultimate power in consolidating databases and engaging with prospects. Now, they’re the experts who can act as the mentor for their clients.

The monomyth brings it all together—just like this section

We’ve greatly shortened the hero’s journey, but it’s still there, structurally. The result is a story that is nice and tidy, a circle with a bow on top. And because you structured the story in a way that is immediately recognizable to the audience, you help customers and prospects personify themselves within your story. And that does more than create a compelling narrative; it also creates a strong sales piece.

If you’re looking to make your success stories epic, let me know. I can be your J.R.R. Tolkien. (But I won’t be as wordy. And there will probably be fewer orcs.)